Dear Eva: The Story of a Camp Greene Veteran During WWI

Published on November 11, 2023

Curious about Camp Greene? Check out our Veterans Day video feature!

By Kayla Chadwick-Schultz

Men and women from all over the country flooded to Charlotte, N.C. after the United States officially declared its involvement in the First World War. Why? Well, their country needed them to serve, and training for that service was taking place at Camp Greene—a newly established military training facility on the western side of the Queen City.

New recruits came to Charlotte from nearly every direction, whether they had just joined up or were recently drafted. Trains rolled in from the South, the West, and the Northeast one after another. Thousands of new faces disembarked at the Seaboard Air Line Railroad Passenger Terminal at 1000 North Tryon Street and made their way west of the small textile town toward modern-day Wilkinson Boulevard. One of those new faces was Joseph B. Mathews, a private from Haverhill, Massachusetts.

During his time at Camp Greene, Private Mathews wrote letters to his girlfriend, Eva, who was a schoolteacher in Haverhill. He began each letter with “Dear Eva” and concluded with whatever signature he felt suited him that particular day. Sometimes, it was a simple “Sincerely, Joe” and other times, it was a formal “J.B.M., Sept Caserne,” alluding to his location within the Camp (Barrack 7) and his improving grasp of the French language. Whichever signature he used, it always seemed to match the mood of his letter, providing Eva unique insight into his psychology.

One of Private Mathews’ letters to Eva (UNC Charlotte).

Now, you may be wondering how I know all of this. Of course, I am not Eva. I did, however, get the opportunity to read Private Mathews’ letters to Eva in The University of North Carolina at Charlotte archives, where they have been generously donated and preserved. The collection includes personal correspondence and memorabilia from Dec. 7, 1917, all the way to Feb. 9, 1919. In these letters, Mathews shares his true feelings about the Army, the facilities at Camp Greene, the Base Hospital in which he worked, and the city of Charlotte as a whole.

While it is impossible to glean the full story of a man through a single year’s worth of letters, this collection allows us to get to know Private Joseph B. Mathews, a Veteran of Camp Greene. Who he was before and who he became after remains a mystery, but his life during World War I exists within the pages of every letter he wrote to Eva and that story is one worth telling.

“This Is a Serious Time”

Soldiers at attention during training (Charlotte Mecklenburg Library).

Considering the date of the earliest letter in Mathews’ collection, he likely arrived at Camp Greene in Dec. 1917, eight months after the U.S. officially entered the war. He was assigned to the Base Hospital—the largest and most active facility on the Camp’s grounds—as a medical officer.

The Base Hospital provided medical services for the soldiers and accommodated up to 1,000 patients prior to its eventual expansion. According to Miriam G. Mitchell and Edward S. Perzel in The Echo of the Bugle Call, “All the buildings were well-heated by stoves, with steam heat in the two operating rooms. Plumbing and sewerage were installed at a cost of approximately $50,000. The huge facility had a section for recreation of the patients (including pool tables), shower baths, a tailor shop, and a barber shop.” The massive size of the hospital was a direct response to Camp Greene’s tremendous population.

Soldiers from every corner of the nation had been sent to Camp Greene to learn how to dig trenches, fly airplanes, operate machine guns, ride horses, and well, just about everything else they needed to know to fight overseas. This training was an essential part of the United States’ war effort, and it moved along steadily at first. Naturally, there were some issues with overcrowding at first, and the winter weather turned out to be harsher than they’d previously anticipated, but all in all the Camp was off to a great start.

Soldiers at Camp Greene’s barber shop (Charlotte Mecklenburg Library).

Then, in Oct. 1917, two sudden deaths shook the Camp. One occurred when a private was shot during target practice, and the other was the result of pneumonia (Mitchell & Perzel). From that point on, Camp Greene was thrust into chaos, and the Base Hospital was at the center of it.

Disease ran rampant, taking advantage of the close quarters and poor weather. By Jan. 1918, the soldiers at Camp Greene were battling an entirely different enemy than those abroad—an epidemic of cerebrospinal meningitis. The outbreak spread so rapidly that Camp had to go into full quarantine before the month was over.

Private Mathews had sent a letter to Eva in mid-January that included a photo of himself. The photo, which was not included in Mathews’ archives, must have reflected his state of mind during this difficult time, as he wrote: “So you think I looked serious in the picture, that is as it should be. This is a serious time, so to speak, and it is only right that we should look that way. However, if I get another chance I will endeavor to smile if it hurts.”

It is difficult enough training for a war, never knowing when you’ll be shipped out and sent into battle. It is even more difficult to conduct that training in the midst of an infectious outbreak. One division lost a number of soldiers to the disease, which had started to spread into the civilian population. The first civilian to die, A.W. Wicker, “probably contract[ed] it from an infected soldier who visited his barbershop” (Mitchell & Perzel). After Wicker’s death, there was no denying that the quarantine was necessary, but the seclusion that stemmed from it took a psychological toll.

There was no escape from intrusive thoughts of death and disease. It was all around them, all the time. Mathews sought comfort in the familiar, often clinging tightly to one of Eva’s sweaters. She’d lent it to him as a reminder of home, and he made sure she knew just how much comfort it brought him during his time away. It brought back fond memories of life in Haverhill, while life in Charlotte became more and more complicated.

“The quarantine is still on and there are all kinds of stories going round,” Mathews wrote to Eva on Feb. 16, 1918. “One day the papers say the entire camp is condemned and will be abandoned and the next day they reverse their words. The camp is in miserable condition there is no doubt of that, the earth being as I have probably said before a slimy red clay which will not absorb the water, thereby causing much inconvenience and they say in the summer would cause a lot of sickness. I hope we are on our way before that time comes, as I would rather nurse wounded men than sick ones. I suppose the mud is just as bad over there, or as these guys say ovah yondah.”

Rain left the camp so muddy that trucks would often get stuck (Charlotte Mecklenburg Library).

From slimy red clay to thick southern accents, Mathews did not paint the most flattering picture of North Carolina in his letters to home. He was exceedingly frustrated by the slow pace of life in the South, often complaining about how long things take. Then again, he complained about nearly everything during those days of quarantine—including the routine dinners of spaghetti or hot dogs or ham and eggs.

To be fair, Mathews received consistent night duty assignments throughout the first quarantine. On Feb. 22, he told Eva that “for the last few days the heavy artillery has been out on the range, and they make considerable noise all day.” He wasn’t sleeping, he was watching people succumb to disease, he wasn’t allowed to go anywhere or do anything outside of the Camp, and he was rapidly starting to lose hope that the quarantine would ever come to an end. He had reached the point of wishing they would just send him over to Europe.

“There Are Times When Anyone Would Have the Blues”

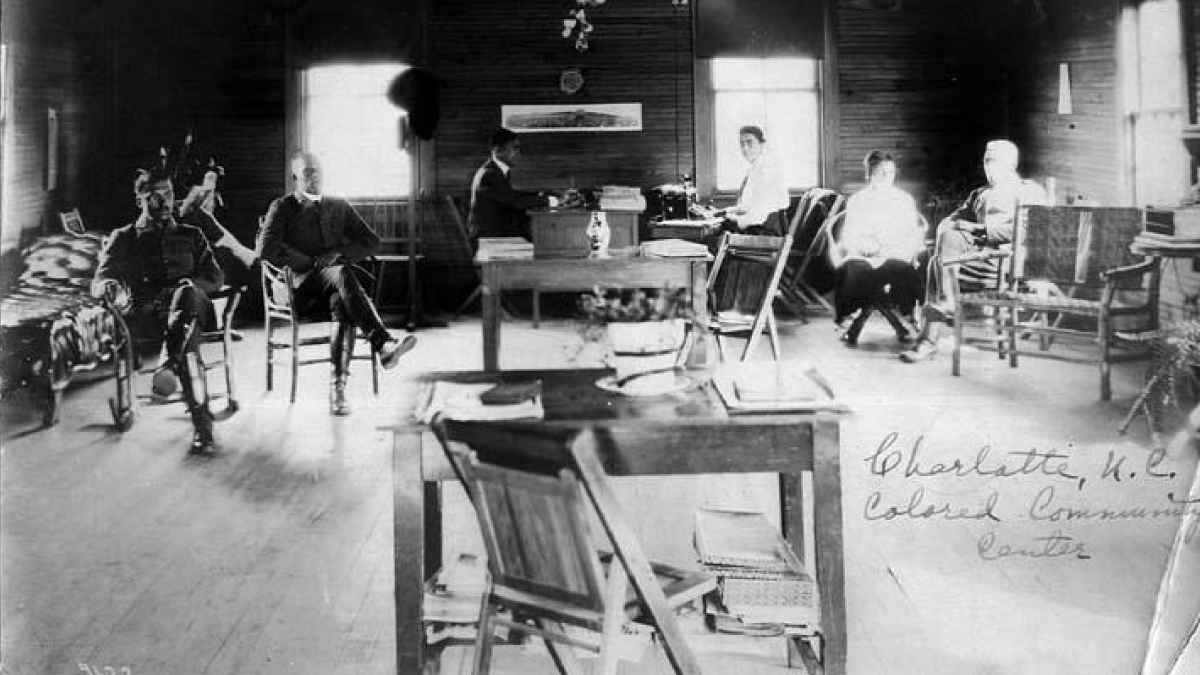

Interior of one of Camp Greene’s many community centers (Charlotte Mecklenburg Library).

Not long after his Feb. 22 letter to Eva, the quarantine was officially lifted. The meningitis outbreak was finally under control, and Camp Greene was eager to get back to normal. However, for Mathews, the experiences of that first winter had already done a good deal of damage to his spirit.

Eva was understandably worried about him, but he did what he could to reassure her in his letters. On Mar. 2, 1918, he wrote, “Thank you for your sympathy but I don’t very often get lonesome. Usually too busy. But you know there are times when anyone would have the blues.” He went on to describe one of those times, detailing a concert that took place on base and the quiet moment of reflection he was able to have afterwards. He stared up at the moon, thinking of Eva and wondering if she would have liked the show as much as he had. “It’s on such times as that that a fellow will be blue,” he admitted. “But it passes in the complexities of life in an army camp.”

Mathews words were true. Loneliness wasn’t what plagued him. He was surrounded by men of “every shape, style, quality, religion, etc.” and was forming new friendships. No, it wasn’t loneliness; it was boredom. It was the sitting still, the waiting, the wondering. Boredom was the enemy that Private Mathews so often faced during his WWI service.

“You know, I am beginning to think that we will be here all summer and gosh how I dread it,” he told Eva. “If we got orders tomorrow for France, I would be troubled to death. But when I think of remaining in this forsaken place in the summer OW.”

Some of the other community buildings at Camp Greene (Charlotte Mecklenburg Library).

His eagerness to do something, even war, began to irk some his new friends at Camp Greene. One in particular, a man named Lawrence who worked with him at the Base Hospital, would often become upset whenever Mathews made these remarks. “I keep telling him I wish they would send us over and he goes wild,” he shared with Eva. He couldn’t understand it. Why would anyone want to stay here, trapped with the wet clay and the diseases, when they could be out in the world making a difference? It didn’t make sense—at least, not at first.

He later discovered why Lawrence was so on edge about the thought of shipping out. Mathews wrote to Eva on Mar. 2, explaining that Lawrence received a letter from his wife then “went out and bought me a cigar because he had just learned he was a father.” He continued, “He sure does think a lot of [home]. I guess he would give his right hand to be back.”

Though Mathews surely missed his girlfriend, as evidenced by the significant number of letters he wrote to her, he didn’t have the same desire to return home that Lawrence had. His sights were set solely on France, while Lawrence spent his days dreaming of the beach where he first met his wife. It was merely a different approach to curing the perpetual boredom of springtime at Camp Greene, because “well, there is not much doing around here now, I mean in the way of excitement.”

Hearing that Mathews had become eager to ship out was a shock to Eva. Clearly something had changed in him between the time he left Haverhill at the end of 1917 and the time he started dreaming of being called into action in the spring of 1918. That change was even more evident when he wrote, “Yes, indeed I remember when I said ‘What do I want to go to France for,’ but that was before I saw Carolina. Now things are entirely changed and even France with all its troubles and tribulations would be welcome.”

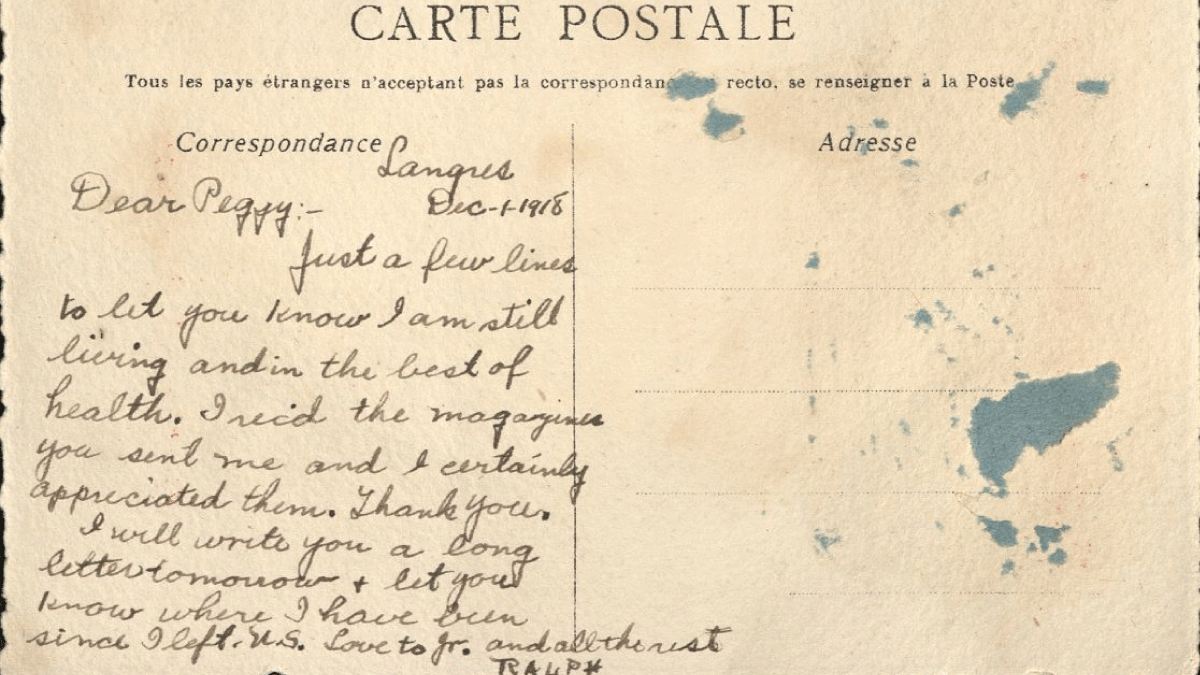

Postcard sent from a Camp Greene soldier in France to a Charlotte resident (Charlotte Mecklenburg Library).

Now, Mathews hadn’t really seen Carolina. He’d seen Camp Greene. Occasionally, the soldiers would venture out into Charlotte to see a show, shop, mingle, etc., but for the most part, Camp Greene was it. It was its own fully functioning city with a barbershop, a post office, a library, various community centers and mess halls, a fully functioning hospital, stables filled with horses, motor vehicles, and eventually it even had newly paved roads. Everything they needed was at their fingertips, which made leaving more of a chore than it was worth. So, they stayed put. They gathered in open fields to listen to radio broadcasts of the World Series. They attended dances organized by the nurses. They played basketball next to the onsite YMCA building. They made a life entirely livable at Camp Greene, but that didn’t make it exciting.

Mathews continued to write to Eva consistently. He never went more than three days without sending another letter. Between March and November, he provided countless updates about life at Camp Greene. The Base Hospital still saw its fair share of ill patients, but the increased staff and establishment of isolation barracks allowed them to keep everything under control. For the medical-officer-in-training, all was rather quiet—frustratingly so—until Oct. 1918.

“There Has Been Quite a Lot of Flu in Town”

A funeral procession at Camp Greene during the height of the flu (Charlotte Mecklenburg Library).

On Oct. 3, 1918, “Governor Thomas Bickett issued the first order in North Carolina’s battle with an enemy which would prove more deadly to the state than the soldiers of the Central Powers” (Harry McKown, NCpedia). Influenza, then known as the Spanish Flu, ravaged the globe near the end of the First World War. Many historians credit a combination of wartime movement and widespread colonization efforts for the rapid spread of the virus, which you can learn more about in Laura Spinney’s book Pale Rider.

Though the first known strain of influenza in N.C. appeared in Wilmington, it quickly overtook the entire state—overwhelming “North Carolina’s medical community and rudimentary public health system” (McKown). Charlotte initially resisted any discussion of putting the city under quarantine, according to Taylor Marks for the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library. Those discussions had begun early in Sept. 1918, prior to any confirmed cases in the city. However, even after the Charlotte News reported over 175 cases the morning of Oct. 3, the city’s health department superintendent, Dr. C.C. Hudson, still argued that quarantine was not necessary (Marks). That all changed when city resident Rosa Stegall died of influenza on Oct. 3, 1918. The city officially put itself under quarantine on Oct. 5.

Camp Greene, having dealt with so much disease already, went into quarantine two days prior. They did not want to take any chances of the flu spreading through the base. Even so, despite their best efforts, “the virus took hold of the camp swiftly” and led to a massive number of fatalities (Marks). As Mitchell and Perzel describe it, “There were so many deaths among the soldiers that the undertakers were swamped. […] Charlotteans remember coffins ‘stacked to the ceiling’ at the railway station waiting for trains to take them home.”

In a strange twist of fate, “North Carolina soldiers in France had carefully followed reports of the flu at home through letters and newspapers. Many soldiers who faced death daily at the front mourned relatives who had died an ocean away from the war” (Tom Belton, NCpedia). Soldiers who never once saw battle were returning home in coffins, as casualties of a different kind of war.

Understandably, Mathews letters to Eva take a notable dip in frequency during the initial days of the flu’s onslaught. His role at the Base Hospital kept him busy with nonstop patient care, and the wintertime quarantine once again took a psychological toll. He still managed to check in occasionally, once noting that “there has been quite a lot of flu in town” and that the camp “sent a few nurses to help in one of the hospitals.”

While his life had become a tedious routine of working, sleeping, and attending funerals, the “powers that be” were working on a solution to the world’s other major problem: the war.

“I Am Sore That I Had to Stay on This Side”

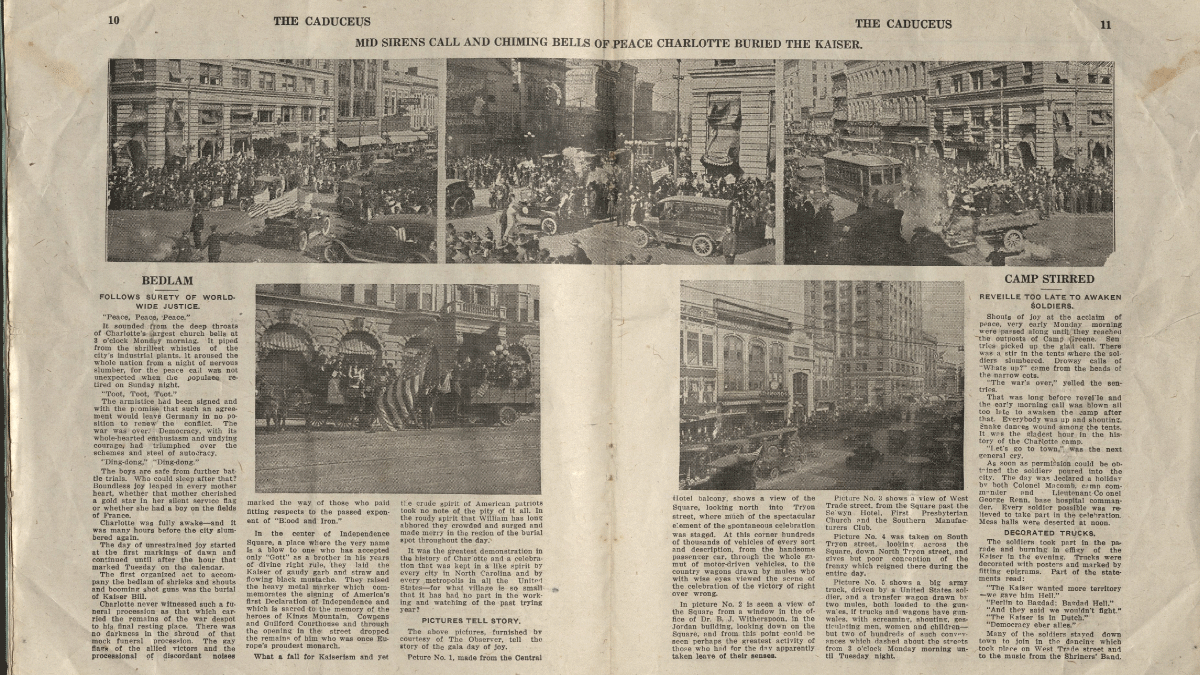

Copy of The Caduceus, the Base Hospital newspaper, detailing the Peace Day celebrations in Charlotte (Charlotte Mecklenburg Library).

Despite the flu still having a prominent presence throughout the city, the people of Charlotte erupted in celebration when peace was officially announced on Nov. 11, 1918. They flooded the streets at the crack of dawn, waving American flags, playing music, and cheering processionals of motor cars. The quarantine had ended back in October, and now the war had ended too. The joy throughout the city was palpable, but not everyone was as happy as one would expect.

Though many soldiers stationed at Camp Greene were excited to get back home to their families, others had difficulty processing the end of a war that they never fought. They had served, they had trained, but they never actually made it to the front. Private Mathews was certainly in the latter.

On Nov. 17, less than a week after the armistice, Mathews wrote to Eva: “I am sore that I had to stay on this side. That sacrifice talk is alright, but you will never hear me bragging because I was in the Army. As a fellow wrote in the Army and Navy Journal the other day, we will never be able to live it down.” The article to which Mathews was referring was a direct response to the idea that soldiers who served during the war but never went abroad would be given a special mark to wear on their uniforms. “This other fellow said he would go to jail before he would wear anything like that,” Mathews explained. “It was bad enough to be kept here without advertising the fact.”

The wound of never having served overseas in World War I was a deep one for Mathews. He struggled to consider himself a true Veteran of the war. What had he done to serve his country if he hadn’t even made it to the frontlines?

Hopefully, in the years following the end of the war, he was able to look back on his time at Camp Greene and realize just how much he had, in fact, served his country. Though he never once charged across No Man’s Land to provide emergency medical attention to a wounded soldier, he still served tirelessly in battles against other enemies. He fought a meningitis outbreak, a mentally taxing bought of boredom, and a global pandemic all within a single year. He healed ailing men and women while stationed away from his loved ones. Private Mathews may not have considered the work he did at Camp Greene a service to the war effort, but it certainly was. Those who remained healthy enough to ship out to France have the staff of the Base Hospital to thank, including Private Mathews.

Base Hospital staff attempting to combat disease in their onsite lab (Charlotte Mecklenburg Library).

However, Mathews’ WWI story didn’t end when the war did. Camp Greene’s Base Hospital remained open for several months following armistice. On Nov. 17, Mathews reported to Eva that there was “talk” of the Base Hospital being converted into a general hospital for sick civilians, so he knew that he would “most likely stay for some time.” Weeks later, on Dec. 5, he sent an update: “Today’s paper is very encouraging. The hospital is going to be used by soldiers from Europe and the camp is going to be a demobilization camp, so if they know what they are talking about we will be here for the rest of our lives I guess.”

It wasn’t the rest of his life, but Mathews did have to stay at Camp Greene to help with operations at the Base Hospital until Feb. 1919. The flu was still a significant concern throughout Charlotte, but it was never as virulent as it had been from Oct. to Nov. 1918. The majority of Mathews’ final months in N.C. was dedicated to helping wounded soldiers returning from Europe.

Whether he was willing to admit it at the time or not, Private Joseph B. Mathews provided invaluable service to the United States during World War I. Where he served is irrelevant. He served, he sacrificed, and he is one of many Camp Greene Veterans who deserve recognition on this Veterans Day.